My Buddhist teacher had a certain enthusiasm for the writings of Samuel - 'Doctor' - Johnson, even running a short seminar on a couple of his poems, to which I was invited, and which I duly attended. I never found Johnson much of a turn-on: I envisaged him as one in a line of British travelling curmudgeons, more recent examples being Alfred 'The Lake District' Wainwright and Cameron McNeish. This might have been extremely uncharitable on my part, but there we have it.....

My Buddhist teacher had a certain enthusiasm for the writings of Samuel - 'Doctor' - Johnson, even running a short seminar on a couple of his poems, to which I was invited, and which I duly attended. I never found Johnson much of a turn-on: I envisaged him as one in a line of British travelling curmudgeons, more recent examples being Alfred 'The Lake District' Wainwright and Cameron McNeish. This might have been extremely uncharitable on my part, but there we have it.....One of Johnson's quotations that sometimes popped up within my world of organised Buddhism concerned second marriages. Getting married once, the Great Sage opined, is understandable. But doing it a second time was foolish in the extreme. It was, he stated, 'the triumph of hope over experience'. In a Buddhist organisation which followed the general pattern, with a tendency to idealise celibacy while gently (or not) disapproving of sexual relationships, Dr Johnson was quoted with a knowing nod of the head. Rock on, Sammie babe, what a shit-hot dude you are, was the general sentiment (though not necessarily expressed in those words exactly).

I was never overly impressed with Johnson's words of marital wisdom. In fact I find them a bit silly. Still, let's go with this a while...... 'the triumph of hope over experience'. Where will it lead us?

Sadly, I found some of these same Buddhists who quoted Johnson with a hearty guffaw less able to apply this notion to other areas of life. It was, I suppose, pretty safe and easy to give a thumbs-up to Johnson when he confirmed ones own pseudo-spiritual dispositions. Yet when 'hope over experience' could be presented to shed light on less comfortable aspects of life, which might indeed require turning the whole thing upside down, it might be better to turn a blind eye.

These were the thoughts that appeared a few weeks back, as I strolled down the Inverness High

Street. It was a week or so before some election or other, and the lamp-posts hung heavy with posters and placards declaring the various parties and some of the candidates. Lib-Dem, UKIP, Tory; Labour, SNP, Green; Scottish Christian Party. I know nothing of his policies - probably what we might expect - but the Conservative had the best name: one Edward Mountain. I looked out for Lucinda Lochan and Peter Precipice, but they were nowhere to be seen.

I was puzzled, confused, by the whole show. For one thing, it hadn't registered that there was an election of any description on. But the question loomed large: do people still believe in this stuff? Ten years ago, when I began work along this very High Street, it was precisely the same. The same tired placards, the same weary attempt to elicit support. Mr Mountain was probably not there a decade ago, but otherwise nothing had changed.

I can kind-of understand a twenty-year old getting involved with this stuff. Youthful, idealistic, experimenting with the ways of the world. But older folk, with a decent beltload of experience wrapped around their by-now protruding bellies? How have they failed to learn? To not see, after decades of unfulfilled promise, shattered expectations, falsely-placed optimism? Nothing has changed. A few details, yes, but viscerally no. This is the real spectacle of hope triumphing over experience.

It requires a fundamental shift in consciousness, one that may be unsettling, disturbing; it may throw your entire view of life and who you are into turmoil. Which is why, I suppose, so many people don't go there. To see that the story of progress, of change, - of hope - is a phantom paraded before our eyes as a deception, a chimera intended to keep us quiet, content in our discontent. To maintain our status, without our even knowing, as sheeple, as some would unkindly have it. The road ahead is not in reality a road at all. It is a hamster wheel. There will be no change on that wheel. It is not intended to change, not designed to change. It simply keeps the system of hierarchy, of control, running smoothly. That is its function.

How many times do folk need their hopes dashed before they 'get it'? To see those moments of historic hope - the Blairs, the Clintons, the Obamas - come to nothing. Of course they come to nothing: that is the point. I have been there - I know. I was one of the multitudes who shed a tear to see Tony Blair out shaking the hands of the people on his first day in office. Gone the terrors of Thatcher and her inept successors. In with the righteous. But within a couple of years, Blair was clearly manifesting as a monster even more terrible than anything Thatcher and her buddies could dream up. These experiences form the node of learning, of going deeper into the fabric, burrowing down into what is really happening.

The torch-bearers of hope are in fact necessary for the continued survival of our broken system. Precisely because of that: they wear the raiment of hope, the promise of better things to come. Without them, the system will surely implode entirely with its own fatigued decadence, its monolithic cliches uttered by puppets almost too world-weary to open their mouths and speak. British politics a few years ago - especially English politics - defined by the pathetic, moronic personages of Cameron, Miliband, and Clegg. A system on the verge of grinding to a complete halt though lack of energy. The system needs its 'hopes' to provide a necessary injection of vitality, of energy. Regardless of their political persuasions, these folk - the Trumps, Farages, Corbyns - are essential, to provide engine fodder. They are viciously, shamelessly, and relentlessly attacked by the mainstream media - I find it a spectacle horrible to watch. Surely, though, a vote for Hillary is a vote with a death-wish: a vote made in glaring blindness, a vote for the system as it rolls out its rubbish over the decades, over the centuries. Well-intentioned people all-too easily rolled over, voting for control, limitation, the death of independent, intelligent thought and being. This is the way: bring out the mavericks, providing a sense of hope for the masses; just don't let them go too far......

In the meantime, let us go forth, with experience our teacher, experience our guide. Do we need this version of 'hope' at all?

Images: Illusion of change: surface waters in motion, while the creatures of the deep continue life regardless. The Skye Cuillin, off Elgol.

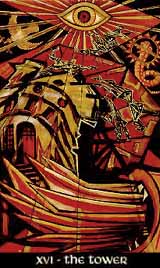

The Star, from Phantomwise Tarot.